Believing

Reprinting old thoughts on faith, mathematical and otherwise

Sunday, November 8, 2020 · 8 min read

I was talking to a dear friend of mine this week, and she unknowingly reminded me of a thought I had last year. I wrote down this essay rawly one November night as an imagined chapter of an imagined book, then by morning forgot it (and the book) unedited. Today’s moment — personal, political, historical — seems as good as any to revisit it.

(Note: Reformatted automatically for web by pandoc. I’m sorry if the delicate math typesetting breaks; then again, for this essay the math is at best incidental to the message.)

The tricky integrals below are known as the Borwein integrals, and, as the Mathematician diligently evaluates them one by one, she is treated to a pattern.

$$\begin{aligned} B_1 = \int_0^\infty \frac{\sin(x)}{x}dx &= \frac{\pi}{2} \\ B_3 = \int_0^\infty \frac{\sin(x)\sin(x/3)}{x(x/3)}dx &= \frac{\pi}{2} \\ B_5 = \int_0^\infty \frac{\sin(x)\sin(x/3)\sin(x/5)}{x(x/3)(x/5)}dx &= \frac{\pi}{2} \\ B_7 = \int_0^\infty \frac{\sin(x)\sin(x/3)\sin(x/5)\sin(x/7)}{x(x/3)(x/5)(x/7)}dx &= \frac{\pi}{2}\end{aligned}$$

The aesthetics of mathematics demand at this point for her to formulate a conjecture, which is that all Borwein integrals $B_n$ are equal to $\pi/2$.

Do you believe this conjecture? Perhaps, but our friend the Mathematician is not so easily satisfied. She presses on and continues evaluating the integrals, and she is rewarded with further evidence.

$$\begin{aligned} B_9 = \frac{\pi}{2} \qquad B_{11} = \frac{\pi}{2} \qquad B_{13} = \frac{\pi}{2}\end{aligned}$$

But when she gets to $B_{15}$, she finds unexpectedly (or is it unexpected?) that it is ever so slightly less than $\pi/2$. The pattern falls apart, the conjecture evaporates, and with it our belief.

The previous essay was on seeing; this one is on believing, the act of believing, the art of believing, the ethics of believing. What does it mean to believe? We might say that to believe is to have beheld proof that expels doubt. I turn to Arnold Ross’ Prologue to his eponymous mathematical summer program held annually at the Ohio State University. He writes,

In an effective program of mathematical studies, students are propelled by eager curiosity to observe and experiment, thus creating new opportunities for observation. In hopes of unearthing deep relationships, students search for patterns among those observations, formulate adventurous conjectures, prune the many conjectures with the sharp ax of possible counterexamples, and then attempt to endow the surviving conjectures with the security of a proof.

To endow with the security of a proof. Proof is comfort in certainty, it is relief, it is contentment in the establishment of truth, the ghoul of doubt having been vanquished. In our so-called “post-truth world,” it can at times be unfashionable to simply believe, and it is understandable for our Mathematician to have demanded proof to assuage her well-placed skepticism.

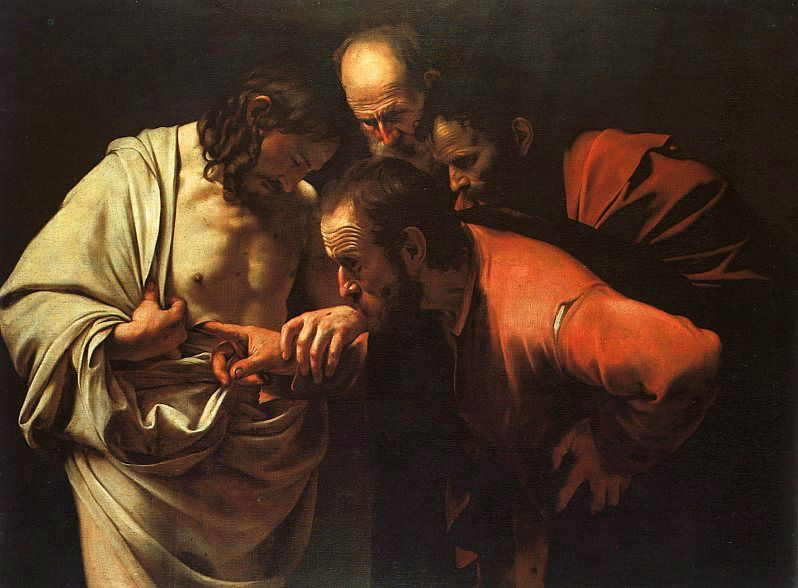

But here matters become complicated. The painting on the right is Caravaggio’s Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601). It depicts the apostle Thomas, who, having missed Jesus’ resurrection, demands proof. Says Jesus, reach and feel my wounds — be not faithless, but believing — because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed (John 20:29). I look at the furrowed brow of Thomas, his all but prosecutorial examination of the evidence, and I wonder: What is the ugly side of proof? Is it right even to use the word belief once you have proof? Or does it then simply fade into the landscape of fact, or, dare I say, reality? I think of those haunting words from the American Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” Self-evident: not “it can be shown that all men are created equal” or “assume for the sake of argument that all men are created equal,” no, this truth is self-evident, it denies proof because proof is unnecessary for an axiom. If even this simple matter of human equality is up for debate, to be quartered by the Devil’s team of reasoned and articulate advocates, then how can we proceed at all?

Christianity is not the only religious tradition to find value in the unproven. I am reminded of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching; I quote now from Stephen Mitchell’s translation of the final verse:

True words aren’t eloquent;

eloquent words aren’t true.

Wise men don’t need to prove their point;

men who need to prove their point aren’t wise.

Or we might turn to an ancient Indian hymn:

But, after all, who knows, and who can say Whence it all came, and how creation happened? The gods themselves are later than creation, so who knows truly whence it has arisen? Whence all creation had its origin, the creator, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not, the creator, who surveys it all from highest heaven, he knows — or maybe even he does not know.

The unproven, the unknown — the unprovable, the unknowable — that is where faith begins, where there are stakes to truth.

What, then, do we make of the 17th-century mathematician Blaise Pascal, who proposed a game-theoretic argument now known as Pascal’s Wager: that a rational person should live as though God exists because it is the prudent option, on the off chance that He indeed does? Or shall we invoke the brilliant 20th-century logician Kurt Gödel, whose seminal work on “incompleteness theorems” introduced the marvelous notion of the provably unprovable theorem — what can we make of Gödel’s “ontological proof” of the existence of God, which has recently been formalized in a computer system and computer-verified, in some sense lending proof to the proof itself? “Ah! Like Doubting Thomas, these men rely too much upon the crutch of rationality,” we might now complain, “searching for and clinging to proof as if the blueness of the sky, the sound of a brook, the smell of a peach were not proof enough of a Creator.”

But even this, I think, is too simple, because to the Mathematician “proof” is more than the expulsion of doubt. Let us play the game of conjecture again. Pick a prime number, and divide it by four. If the remainder is one, try to write the prime number as the sum of two perfect squares:

$$\begin{aligned} 5 = 4\cdot 1 + 1 &= 2^2 + 1^2 \\ 13 = 4\cdot 3 + 1 &= 3^2 + 2^2 \\ 17 = 4\cdot 4 + 1 &= 4^2 + 1^2 \\ 29 = 4\cdot 7 + 1 &= 5^2 + 2^2\end{aligned}$$

Can this be done with all primes?

You might be more cautious to believe this time, so let me just tell you: it can, the observation is known as Fermat’s theorem, and I can supply two proofs. The first is an elegant argument that relates sums of squares to points on a grid, and reasons carefully about the geometry of that grid to conclude that a point with the desired properties must exist. The proof is enlightening, it reveals among other things the importance and origin of that number 4 that smiles so mysteriously in the theorem’s statement. Knowing the deeper mathematical structure at work, we can begin to generalize Fermat’s theorem in new directions; the theorem becomes in a sense just one shadow cast by this structure.

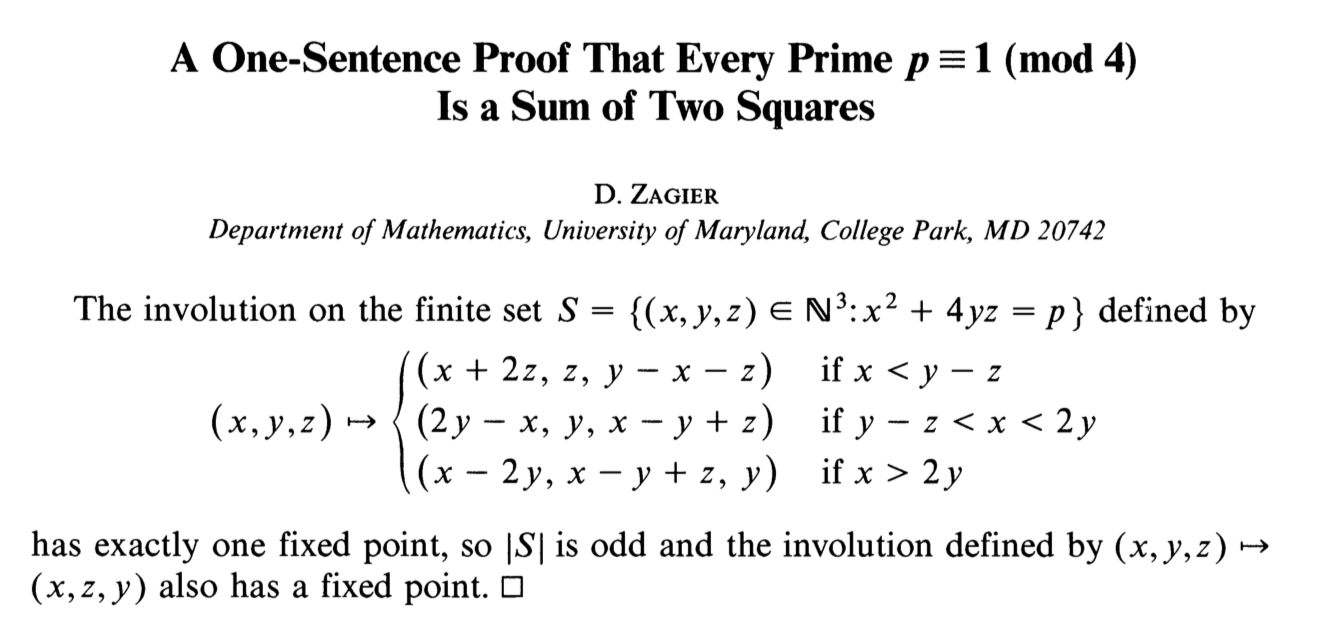

The second proof, due to Zagier, was published in 1990 as a single sentence, and is reproduced in its entirety on the right. It hallucinates for us a truly bizarre object, asserts that it has a certain symmetry that forces there to be an odd number of solutions to the equation $x^2 + (2\cdot y)^2 = p$, and, as zero is not odd, concludes that there must be at least one solution. This is one of the strangest proofs I have ever seen; it provides absolutely no insight into why the theorem is true — though it certainly assures me that it is true. Here it is not the theorem, but rather the proof that is the shadow.

I show you these two proofs to suggest that not all proofs are created equal. The great mathematician Paul Erdős spoke of The Book, wherein God wrote the most elegant, insightful proof for every theorem of mathematics. “You need not believe in God,” he would say, “but you should believe in The Book.” A professor of mine once asked me if I would like a copy of “The Abridged Book,” which for every conceivable conjecture simply lists whether or not it is true. It is a shortened form of the Book, so we can agree to treat its word as proof enough — or perhaps it only provides succinct, convincing but unilluminating proofs in the style of Zagier’s — but it says no more than “true” or “false.” This is not an idle fantasy: already we have found fragments of The Abridged Book in the form of long computer-generated proofs, such as the proof of the Four-Color Theorem, which no human could ever check by hand.

Here is the difference between The Book and The Abridged Book: one would occupy the Mathematician’s mind for decades, the other would be immediately cast aside as useless. To the Mathematician, the quest for a proof is not to establish that a theorem is true, but rather why. The proof is not in the pudding, the proof is the pudding.

This winter I spent some time at a planetarium near Stanford, and I was told by the announcer that the nearest star outside our solar system, Proxima Centauri, is over twenty trillion miles away. Twenty trillion! said the announcer, isn’t that amazing? And I thought — well, is it? Would I be ten times as amazed if Proxima Centauri were two hundred trillion miles away instead? Surely not. I am not sure what to do with that number. I suspect that you are not, either, because as humans we are not equipped to appreciate the celestial scale.

Let us agree then that there is really nothing interesting about that number “twenty trillion” — ah, except for one thing, which is that we know it at all; that we, earthbound, can measure the distances to the stars. On a cloudless night the stars on the horizon appear to follow you as you drive by the streetlights; really, it is the streetlights passing you that create the illusion of relative movement, and the rate of this movement depends on how far away the streetlights are, as a consequence of elementary geometry. The same effect occurs at the celestial scale: as the Earth moves around the Sun distant stars appear to follow us in relation to the nearest stars, a delicate quiver in the stars, and from this effect we can measure the distance to Proxima Centauri. The streetlights are Proxima, our vehicle is Spaceship Earth. To contemplate this, the consistency of geometry, in the small and in the large, is to me a spiritual experience that assures me that I am governed by the same laws of parallax that govern the stars I came from; that is, it is not just all men but all entities that are created equal before mathematics.

There is a poem of Robert Frost’s, “Choose Something Like a Star,” where the speaker pleads for a star to tell him how it burns

And it says “I burn.”

That’s all it says, but then the speaker continues

But say with what degree of heat.

Talk Fahrenheit, talk Centigrade.

Use language we can comprehend.

Tell us what elements you blend.

Frost reminds us of the dignity in the silence of the stars, and that would be all well and good except for one thing: that’s not how stars are. Stars speak to us when they radiate across time and space, and they speak openly to anyone with a telescope. It falls on us — that is, on humanity — to listen, to hear not only the temperature and elemental composition of the stars, but also their biographies, the stories of their births and their deaths.

In the afterword to Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard writes

In October, 1972, camping in Acadia National Park on the Maine coast, I read a nature book. I had very much admired this writer’s previous book. The new book was tired. Everything in it was the dear old familiar this and the dear old familiar that. God save us from meditations. What on earth had happened to this man? Decades had happened, that was all. Exhaustedly, he wondered how fireflies made their light. I knew—at least I happened to know—that two enzymes called luciferin and luciferase combined to make the light. It seemed that if the writer did not know, he should have learned. Perhaps, I thought that night reading in the tent, I might write about the world before I got tired of it.

To write about the world before you get tired about it. The Mathematician is not tired of the world, will never be tired of the world, because she knows the world will never stop speaking to her.

And yes, even though Nature has over the course of this affair revealed for us some Truth — the numerical distance to a star, its numerical temperature — it is not that Truth but rather the revelation that was the true blessing; the number, the Truth, it is just a byproduct, a projection. I wonder whether in the moment of looking into Christ’s wounds Thomas thought at all about the little matter of the resurrection’s authenticity; I wonder if I, seeing Thomas fall to his knees in understanding, would not myself wish to doubt again so that I, too, could be shown the light. How we know is the light and what we know the shadow; proof is the light and theorem is the shadow — this is the Mathematician’s defense of her art.