Coding the Mandelbrot Set

A mirror of a post written a long time ago in a galaxy far away.

Saturday, January 10, 2015 · 5 min read

I wrote this post a long time ago. I had become obsessed with the Mandelbrot Set after reading Professor Stewart’s Cabinet of Mathematical Curiosities, and had spent the better part of a weekend scouring the Internet for information on how to plot it. That is, information I could understand at that age. Watching the correct Mandelbrot Set appear line-by-line over the course of three hours on my mom’s old Mac was one of the more exhilerating computer-science experiences I have had.

The post first appeared on the Scratch forums on April 20, 2011 along with its accompanying Scratch implementation. In the interests of documentation and preservation, I decided to post a copy of this on my blog. Despite many temptations to change things—grammar, spelling, wording, and even some technical details—the text is identical to that posted on the forums. The purpose of posting this is not to convey the actual content to an audience, but to remind myself of how I sounded in the past and to reflect on how I sound now.

Since I do not, of course, retain a copy of the original BBCode, the text has been reformatted in Markdown. Code is left unchanged, though I was tempted to rewrite scripts using the wonderful Scratchblocks2 renderer (this post predates even the original Scratchblocks). I have also made an effort to convert the equations contained herein to MathJax/LaTeX-worthy formats to facilitate reading. This is, of course a tradeoff: I lose the original formatting of the equations (which was delightful in itself) and make the text significantly less legible in its Markdown source. I hope I have made the right decision here. The original equations can always be viewed at the archive linked above.

This is a guide on plotting the Mandelbrot Set. It’s divided into 3 parts: What is the Mandelbrot Set?, Understanding the Algorithm, and Programming the algorithm. Here is a project on plotting it, if you don’t get it.

What is the Mandelbrot Set?

The Mandelbrot Set (M-Set in short) is a fractal. It is plotted on the complex plane. It is an example of how intricate patterns can be formed from a simple math equation. It is entirely self-similar. Within the fractal, there are mini-Mandelbrot Sets, which have their own M-Sets, which have their own M-Sets, which have their own M-sets, etc.

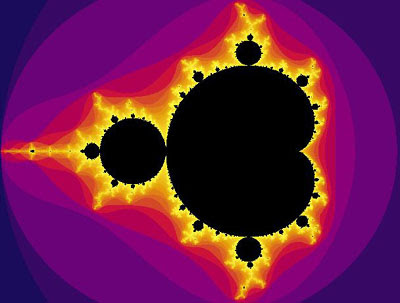

Though most representations of the M-Set have color, only the black bit is part of the set. The color is to basically show how long it took to prove that that point wasn’t in the set. However, these form cool patterns, too.

Here are some pictures:

Only the set:

With color:

Understanding the Algorithm

The M-Set is generated using the algorithm:

\[ Z_{n+1}=z_{n}^2 + C \]

Here, both $ Z $ and $ C $ are complex numbers. What are complex numbers? They’re, put simply, square roots of negative numbers. Since negative numbers can’t have square roots, we created ‘complex’ or ‘imaginary’ numbers to deal with it. ‘$ i $’ (pronounced iota) is the symbol for $ \sqrt{-1} $. Complex numbers are expressed as multiples of $ i $, like $ 3i $. They are graphed on a number line perpendicular to the number line we all know. The resultant plane is called the complex plane, and is where we will graph the Mandelbrot Set.

The complex plane:

1i

-1 0 +1

-1i

Complex numbers are defined as the sum of a real number and an imaginary number. Examples are $ 3i + 1 $ or $ 4i - 2 $.

In this expression, C is the complex number for which you are testing whether or not it’s in the M-Set (it will define a single point on the complex plane — C is a real number plus an imaginary one, remember?). Here’s how you use it: You set Z to 0. Then set $ Z $ to $ Z^2 + C $. We call this action iteration. For example, if C was 3 (I’m using a real number for simplicity), $ z $ would be:

\[ 0 \] \[ 0^2 + 3 = 3 \] \[ 3^2 + 3 = 12 \] \[ 12^2 + 3 = 147 \]

etc.

If you did this many, many times, there are two possibilities for $ Z $ — it escapes to infinity, or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t escape, it is in the set. This looks hard to calculate—how can we know whether it reaches infinity? For all we know at 1000000000 iterations it’ll be a normal, but after 1000000001 iterations it starts constantly doubling. Fortunately, we know 2 other things:

It has been proved that if Z ever gets higher than 2, it will escape to infinity

If it does escape, it’ll do so normally within 50 iterations. More will make a more accurate picture, but it will slow the script down considerably. 50 is a good number.

So now, all we need to do is repeat $ Z^2 + C $ 50 times and see how high it is. Great!

Programming the Algorithm

That’s all very nice, but there’s a catch (isn’t there always?)—this uses complex numbers, and Scratch—make that any programming language—doesn’t allow square roots of negative numbers. Try it yourself. You’ll get a red Error!. So how do we avoid this? Well, remember how a complex number is a real number plus an imaginary number, and an imaginary number is just $ \sqrt{-1} $? Well, that means we can split any variable, say $ Q $, into two variables: q-Real and q-Complex, or abbreviated, $ qR $ and $ qX $. We also know that $ qX $ squared is real, because $ i^2 $ is $ -1 $ which is real, and the coefficient is real anyway (here, coefficient is the 3 in $ 3i $. This means now we know how to square complex numbers to get real numbers. So, let’s take a look at the algorithm:

\[ Z_{n+1} = Z_{n}^2 + C \] \[ =(zR + zX)^2 + cR + cX \] \[ =zR^2 + zX^2 + 2zR*zX \left\{\text{by opening the brackets}\right\} + cR + cX \]

If you think carefully, $ zX $ can only be represented by its coefficient. This is because $ zX^2 $ is real, and $ 2*zR*zX + cX $ (all the complex terms) can be represented by the coefficient, which is again because $ zX^2 $ is real. So, we never ‘need’ the value of $ i $, which is a huge relief. Now we can start coding!

We need a sprite to move through every point on the stage. That’s easy:

set x to -240

set y to 180

repeat 360

set x to -240

change y by -1

repeat 480

change x by 1

. . . Insert coding here . . .

end repeat

end repeat

See where I put . . . Insert coding here . . .? That’s where we need to code

our algorithm. From now on, all the coding I show you will be in that segment.

Starting off,

set cR to x position/120 {because real numbers are on the horizontal number line. '/120' is to set the magnification.}

set cX to y position/120 {because imaginary numbers are on the vertical number line. '/120' is to set the magnification.}

set zR to 0

set zX to 0

set r to 0 {r will be the number of repetitions. You'll se why this will be helpful pretty soon}

This’ll set up all our variables. Great. Now for the hard part.

For the calculation, we need to set $ zR $ to $ zR^2 + (zX^2*-1 \{\text{because i^2 is -1}\}) + cR $, and set $ zX $ to $ 2*zR*zX + cX $. We get this just by grouping them on the basis of their complexness. Complex values get added into zX, the rest into zR.

set old_zR to zR {this is because zR will change, and when evaluating zX we'll get the wrong value of zR}

set zR to (zR*zR) + -1*(zX*zX) + cR

set zX to 2*old_zR*zX + cX

change r by 1 {'cause r counts the repeats}

But, before we put that in, we need to know how many times to iterate. Iterate means repeat, so we need to put this into a repeat. We know that by 50 iterations, we can be pretty sure whether $ zR $ will ever exceed 2 or not. The problem is that it may exceed 2 very early, and approach infinity, causing Scratch to freeze because the numbers get out of hand. So, we need a ‘if I’m over 2, stop me right away’ repeat. This is exactly why we needed $ r $.

repeat until [r > 50] or [zR > 2]

will do the job. [r > 50] says it repeats 50 times, [zR > 2] says if it's over 2, stop repeating.

Now, we can finally tell whether the point you chose is in the Mandelbrot Set or not. Whew! This part is really simple, so I’m not going to explain it (much).

if zR > 2

set pen color to [black]

pen down

pen up

else

set pen color to [r] {because non-set points are colored based on how long it took to establish C wasn't part of the M-Set}

set pen shade to [50] {because black has a shade of 0, and so all colors will end up black}

And we’re done! Congratulations!

You can get the whole project here.