How Random is xkcd?

A blatant abuse of statistics.

Friday, March 20, 2015 · 6 min read

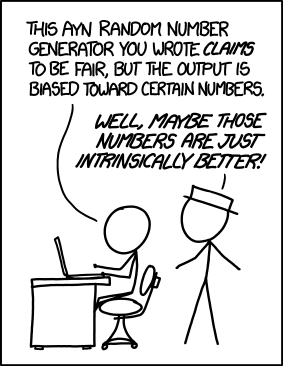

Apparently Randall Munroe gets a lot of messages saying that the “random” button on xkcd is biased.

2015-03-19 16:47:00 Hobz also, Randall, the random button on the xkcd frontpage is frustratingly un-random

2015-03-19 18:50:52 ~Randall it’s random.

2015-03-19 18:50:59 ~Randall people contact me constantly to tell me that it’s not

2015-03-19 18:51:17 ~Randall which is a nice illustration of that mental bias we have

I thought I would do a little investigating to see just how random xkcd is.

Making consistently random numbers (yes, that sounds weird) is really important in things like cryptography. Unrandom random numbers can cripple an otherwise secure network. So there’s a surprisingly large amount of work dedicated to randomness.

There are services like random.org which pride

themselves on randomness, and HotBits,

which lets you order random bytes that are generated from radioactive decay. A

lot of applications use /dev/urandom/, which is an OS-level random generator

that uses all sorts of sources of entropy such as network noise, CPU heat, and

the current weather in Kansas.

Unfortunately, it’s really hard to tell whether numbers are random or not. Of course, patterns can creep into random numbers. But more annoyingly, a glaringly obvious pattern might just be accidental. My favorite example of this is the Feynman Point, which is a series of lots of 9s that appears somewhere in the (very unpredictable) decimal expansion of pi.

There are a bunch of established ways to test the randomness of a random number generator (such as the excitingly-named Diehard tests). They all test for features that ostensibly random data should have. For example, a random stream of bits should have almost as many ones as zeros. Not all tests are that obvious, though, and statistics can be very slippery and unintuitive when it feels like it.

NIST (the National Institute of Standards and Technology, who deal with things like how long an inch is and how to backdoor elliptic curves) publishes a standard for randomness based on such tests, and distributes software that runs these tests on datasets.

I wrote a Python program to download 10,000 xkcd-random numbers (yay

requests!), and converted them into bitstrings. Then, I fed them to the NIST

Statistical Test Suite.

The results are below:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RESULTS FOR THE UNIFORMITY OF P-VALUES AND THE PROPORTION OF PASSING SEQUENCES

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

generator is <data/data.xkcd.long>

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9 C10 P-VALUE PROPORTION STATISTICAL TEST

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5 8 7 13 9 8 13 12 15 10 0.437274 100/100 Frequency

10 10 11 9 10 16 10 6 8 10 0.759756 99/100 BlockFrequency

5 12 13 10 7 10 10 10 9 14 0.699313 100/100 CumulativeSums

8 3 13 9 9 14 13 8 12 11 0.366918 98/100 CumulativeSums

8 12 11 3 9 8 17 12 9 11 0.224821 100/100 Runs

7 8 8 6 15 9 12 9 15 11 0.437274 99/100 LongestRun

7 8 7 16 0 25 0 25 0 12 0.000000 * 100/100 FFT

3 10 4 19 15 0 18 6 10 15 0.000009 * 100/100 Serial

9 14 10 2 14 8 6 10 16 11 0.080519 100/100 Serial

16 1 5 9 6 0 6 0 10 47 0.000000 * 93/100 * LinearComplexity

The important column here is “Proportion”, which shows the pass rate. They’re all stellar.

If that isn’t convincing, I ran an obviously nonrandom sample for comparison. This is what NIST’s STS thinks of the first 100,000 bits of Project Gutenberg’s plaintext version of Romeo and Juliet:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RESULTS FOR THE UNIFORMITY OF P-VALUES AND THE PROPORTION OF PASSING SEQUENCES

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

generator is <data/data.rnj>

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9 C10 P-VALUE PROPORTION STATISTICAL TEST

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

95 3 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0.000000 * 25/100 * Frequency

55 14 10 6 6 3 1 1 3 1 0.000000 * 64/100 * BlockFrequency

94 3 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0.000000 * 28/100 * CumulativeSums

93 4 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0.000000 * 30/100 * CumulativeSums

51 7 10 10 4 4 2 5 2 5 0.000000 * 61/100 * Runs

90 8 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.000000 * 44/100 * LongestRun

92 2 2 2 0 1 0 1 0 0 0.000000 * 23/100 * FFT

100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.000000 * 0/100 * Serial

100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.000000 * 0/100 * Serial

14 2 2 7 11 0 4 0 11 49 0.000000 * 95/100 * LinearComplexity

Much worse.

I encourage you to play with the STS code. It lets you do all sorts of other neat things, like testing bitstrings for common “templates” and reporting if too many are found. It also segfaults all over the place, which is actually very disturbing considering that it’s technically part of the US government’s computer security project.

In any case, we’ve established that xkcd’s random generator is reasonably unpredictable and unbiased. As it happens, they’re using the Mersenne Twister, which is a well-established pseudorandom generation algorithm.

So why does the random number generation appear so biased when we’re idly refreshing on lazy Sunday nights? Part of it is, of course, human nature. We like to see patterns everywhere.

But here’s a more concrete, mathematical explanation. The conceptual idea is that in the beginning, hitting “random” is likelier to hit an unread comic, but once you’ve seen more and more of them, you get repeats. Let’s try to quantify this: we’re going to calculate the expected value of the number of times you need to hit “random” until you have seen every single comic. You may have seen this problem in the context of “how many times do you need to roll a die until you have rolled all six faces at least once?”.

Expected value is the average value of some random variable if you do an experiment lots of times. For example, if you roll a die gazillions of time, the average number you’ll get is $ (1+2+3+4+5+6)/6 = 3.5 $, so that’s the expected value.

We’re going to calculate the expected number of times you hit “random” by calculating the number of times you need to hit it to get the first, second, third, and (in general) nth unique comic. Then, because of a useful property of expected values, we can just add them together until $ n = 1500 $ (there are 1500 comics published as of right now) to see how long, as of today, this process would take.

If you’re looking for your $ n $th unread comic, each time you hit “random” you have a $ 1 - n/1500 $ chance of getting a fresh one. This is a geometric probability distribution, which is Math for “you keep trying something with a constant probability until it succeeds”. For geometric probability distributions, the expected value is one over the probability (though I’m not going to prove it here, this intuitively makes sense: you would expect to have to roll a die around 6 times until you get your first 1, or to flip a coin twice until you get your first heads).

Anyhow, for the nth comic, the expected number of clicks is $ 1500/(1500-n) $. Adding these up for each $ n $, we have this monstrosity:

\[ \sum_{n=1}^{1500} \frac{1500}{n} = \frac{1500}{1500} + \frac{1500}{1499} + \dots + \frac{1500}{2} + \frac{1500}{1} \]

This works out to, on average, 11836 clicks. That’s a lot of clicks.

As common sense dictates, the more times you have clicked “random”, the less likely it is for you to hit a new comic. And that’s why Randall’s random button seems biased.

One more bit of statistics: if you’ve taken a probability class, you might have heard of the birthday problem. That is, say you have a party with $ n $ people. What is the probability that some pair of people at the party share a birthday?

It turns out that if you have just 23 people, the probability is already 50-50. This is somewhat counterintuitive; most birthday parties only have one birthday boy! The fallacy is that the problem isn’t asking if some particular person shares a birthday with someone else. It’s asking if any two people share a birthday.

The birthday “paradox” turns out to be important in cryptography, especially when looking for hash collisions. The number of hashes you need to generate before you hit a collision is similar to the number of people you need at a party before some pair shares a birthday—much smaller than what you would expect.

In terms of xkcd-surfing, this helps answer the question “how many times will I hit random before I see a repeat?”.

There are plenty of good explanations for the math behind the birthday problem online (Wolfram Mathworld and Wikipedia)—but if you don’t believe the number 23 quoted above, it’s worth spending some time trying to solve it yourself just to understand what’s really going on (it’s not hard). I’m just going to dump the formula here without any explanation.

For 1500 comics, the probability that you get a repeat after $ k $ clicks is:

\[ 1 - \frac{1500!}{(1500-k)!1500^k} \]

Throwing this at WolframAlpha, we see that after only 45 clicks, you have a 50-50 chance of seeing a duplicate comic. Put a different way, there are even odds that the last 45 comics you have seen contain a duplicate pair somewhere in there.

So we’ve empirically validated that xkcd’s RNG is as close as we can expect for something statistically random. We’ve also seen two reasons why it feels biased.

But on a deeper and much more important level, we’ve seen how counterintuitive and messy the random-number business is, and how statistical facts can trick us into seeing patterns that aren’t there.

P.S. My methodology for these experiments probably not the best, since I have no formal statistics background. If you want to check out the code used or a dump of my dataset, leave a comment below and I’ll send it to you.