Meet the Robinson

An introduction to automatic theorem proving.

Sunday, October 18, 2015 · 8 min read

On October 10, 1996, a program called EQP solved a problem that had bothered mathematicians since 1933, almost 60 years ago. Using a powerful algorithm, EQP constructed a proof of a theorem on its own. EQP ran for around 8 days and used about 30 Mb of memory.

The theorem was known as Robbins’ conjecture; a simple question about whether a set of equations is equivalent to the boolean algebra.

You read more background here or on the New York Times archives. You can also view the computer-generated proof here.

This article (or series of articles) will shed some light on how EQP worked: the fascinating world of automatic theorem proving.

Along the way, we’ll explore ideas that have spanned millennia: formal logic, Gödel’s (In)completeness theorem, parsing, Chapter 4.4 of The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, P=NP?, type theory, middle school geometry, Prolog, and philosophy. Over time, we’ll build up the tools needed to express a powerful theorem-proving algorithm: Robinson’s Resolution.

This isn’t meant to be very notation-heavy. I’ve avoided using dense notation in favor of sentences, hoping it will be easier for people to jump right in.

Exercises are provided for you to think about interesting questions. Most of them can be answered without a pencil or paper, just some thought. Some of them are introductions to big ideas you can go explore on your own. So really, don’t think of the exercises as exercises, but as the Socratic part of the Socratic dialogue.

- Exercises will be formatted the way this sentence is.

If you want a formal education in all this, consult Russell and Norvig’s textbook, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. All I’m writing here I learned on my adventures writing my own theorem prover, lovingly named Eddie.

To prove theorems, we really need to nail down what words like “prove” and “theorems” mean. This turns out to be kind of tricky, so the first post will be devoted to building up some formal logic: mainly vocabulary and big ideas.

Logic begins with propositions. Propositions are sentences that can be true or false, like “Charlie is a basketball player.” or “Two plus two is five.”.

Except, we don’t necessarily know whether a proposition is true or false. Do you know whether Charlie is a basketball player? I don’t.

Then again, there are certain propositions that everyone knows are true. Propositions like “Either it is raining or it is not raining.”.

How do we know that that’s always true? One way is to list out all possibilities and see what happens:

| It is raining. | It is not raining. | Either it is raining or it is not raining. |

|---|---|---|

| True | True | True |

| False | True | True |

| True | False | True |

| False | False | True |

This sort of listing is called a truth table, and it assigns a truth value for each proposition. Each row is called a model.

Statements like these are called tautologies, and they seem to be pretty meaningless (like “no news is no news” or “if you don’t get it, you don’t get it”). We’re also going to refer to them as valid statements.

A statement could also be never true. These are called invalid statements.

Finally, a statement could possibly be true: these are called satisfiable. A satisfiable sentence is a sentence that could be true if certain propositions are true and others are false. Here’s an example:

| It is raining. | Mark is strong. | It is raining and Mark is strong. |

|---|---|---|

| True | True | True |

| True | False | False |

| False | True | False |

| False | False | False |

As we get into more complicated stuff, it’ll be annoying to write out these propositions in full. Also, sometimes we will want to talk about an arbitrary proposition, like a variable. So, we’re going to use capital letters to denote propositions. For example, I might say “let P be the proposition ‘It is raining.’”. You can then replace all instances of P with that proposition.

- If a statement is not invalid then it is (choose one: valid/satisfiable).

- Relate the above statement to why the opposite of “everyone came to the party” isn’t “nobody came to the party”. State the correct opposite.

- Relate the above to De Morgan’s Laws, if you’ve heard of those.

So I cheated a bit above; I made up sentences like “It is raining and Mark is strong.” without talking about what “and” really means.

Logicians generally use three main ‘operators’: “and”, “or”, “not”. You can use them to modify or join propositions and form bigger propositions (called sentences or formulas or expressions).

- Explain why having both “and” and “or” is redundant. Explain why we have them anyway.

We have symbols to denote these: we use ¬A for “not A”, A∧B for “A and B”, and A∨B for “A or B”. It’s easy to get those last two confused at first; a nice mnemonic is that ∨ looks like a branching tree, which relates to choice (“or”).

In practice, this lets you turn sentences like “Either I am dreaming, or the world is ending and we do not have much time left.” into something like:

D ∨ (W ∧ ¬ T)

- Explain how ∨ relates to ∪ and ∧ relates to ∩ in set theory. Use a Venn diagram.

- For some fun trivia, look up the difference between a Venn diagram and and Euler diagram. Which mathematician came first? I’m going to refer to Euler diagrams instead of Venn diagrams in the rest of this post.

Another operator is implication. We say “A implies B” if B is true whenever A is true. We denote this in symbols with “A ⇒ B”.

- Draw an Euler diagram for A ⇒ B.

- Rewrite A ⇒ B in terms of “or” and “not”. Use your Euler diagram to help you figure this one out.

That last exercise was a little tricky. How did you know your answer was correct? The foolproof way is to write out a truth table for A and B. But, as you can imagine, that gets tedious as you add more and more propositions.

- Prove De Morgan’s Laws by showing that the truth tables of both expressions are identical.

- How many rows are in a truth table of an expression with 10 propositions?

And it gets worse. What if you have an infinite number of propositions? Like “1 is a positive number” and “2 is a positive number” and so on ad infinitum? Infinitely long truth tables sound gnarly. Clearly, we need a better way to deal with this.

The better way is to think in terms of rules of inference. Rules of inference are ways to transform expressions.

A rule of inference you’ve probably used is modus ponens, which states that if you have “P is true, and P implies Q” then you can deduce that “Q is true”.

For example, if Rover is a dog, then Rover is an animal. Since Rover is a dog, we can deduce that Rover is an animal.

- Rewrite “P is true, and P implies Q” in terms of the operators introduced above.

- Create a truth table for that where the columns are “P”, “Q”, and “P is true and P implies Q”.

- Circle all the rows where the last column is “True”, and check to see that “Q” is true in those rows.

- Prove, with a truth table, that ((P⇒Q)∧P)⇒Q is a tautology.

Rules of inference are often written as fractions where the preconditions (also called antecedents or premises) are written as numerators and the results (also called consequents or conclusion) are written as denominators:

\[ \frac{P,\; P\implies Q}{Q} \]

Note that sometimes we elide the “and” from a series of premises.

- Write a pair of rules of inference that correspond to De Morgan’s Laws.

- Why are rules of inference written as fractions? Come up with a “cancellation” rule that allows you to chain rules of inference where one’s conclusion is the other’s premise.

- Are rules of inference reversible? Write a reversible and irreversible rule of inference.

- In the rule of inference written above, “P” and “Q” don’t represent specific propositions. What do they represent? Write an English sentence that expresses what they represent. Explain why they are called metavariables. Explain how this relates to pattern-matching.

- Explain how this allow us to use a finite truth table to say things about a potentially infinite set of propositions.

A rule of inference is valid if its conclusions are true in all models where its premises are true.

- Write an invalid rule of inference.

- Write an invalid rule of inference that looks valid at first glance by modifying modus ponens. Look up modus tollens, affirming the consequent, and denying the antecedent. For extra credit, use one of these fallacies in your homework and see if your teacher notices.

A rule of inference should also be consistent, which means you shouldn’t ever be able to use that rule of inference to prove both A and not-A.

- Write an inconsistent rule of inference.

Now, finally, we have the tools to talk about proofs. In a “logical system”, you pick certain axioms, which are propositions that seem true. Then you use your rules of inference to show that those axioms imply other exciting things. Theorems are propositions that you can prove in this way, and proofs are chains of these rules of inference. A statement that has a proof is a theorem.

- Explain how you can represent parsing as a logical system. In particular, come up with an explicit connection between (1) production rules and rules of inference, and (2) theorems and strings that match a grammar.

- We talk about parse trees, not parse chains. Should we talk about proofs in terms of trees of rules of inference, rather than chains of rules of inference?

One of the first logical systems was Euclid’s postulates. With a handful of simple axioms that anyone would agree with, Euclid built up all of geometry. While other philosophers (like Thales) had come up with the same results Euclid had centuries before him, Euclid put all that machinery on a solid, rigorous foundation. In a future episode, we might even go ahead and encode Euclid’s axioms in formal logic.

Meanwhile, in the early 20th century, a crisis was brewing. People were coming up with all sorts of messy paradoxical results. The biggest one was Russell’s Paradox, which went somewhat like this:

Imagine the set of all sets that don’t contain themselves. So, for example, the set {1} is in that set, while the set of all sets is not in that set (because it contains itself). Does this weird set contain itself?

- Wrap your head around that by coming up with an explanation for why it does and doesn’t contain itself.

- Explain how this relates to the Liar’s Paradox, “This statement is false.”

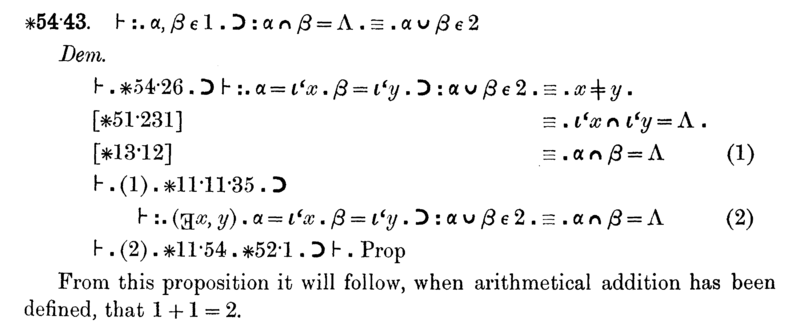

With these messy loopholes popping up all over the place, Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell decided it was a good idea to take matters into their own hands and put math on solid foundations like Euclid did centuries before.

The result was the Principia Mathematica*, a treatise that stated a set of axioms and rules of inference for set theory, and then built up arithmetic and the rest of math from that.

The Principia was careful to avoid any sets that contained themselves, and so Russell’s Paradox and the Liar’s Paradox could be avoided.

- How does the Liar’s Paradox relate to sets that contain themselves?

It seemed like a sweet deal, until Kurt Gödel came along and broke everything.

(*We stopped using the Principia, by the way. Most mathematicians use the axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, abbreviated ZF. But it still has the problems Gödel discovered.)

Modus ponens isn’t a magic bullet.

- Given “A and B”, can you use just modus ponens to prove “A or B”? Does that mean “A or B” is false?

- Come up with another statement that cannot be proved under modus ponens.

This is really bad, if you think about it. It means that there are statements that can be true according to our axioms, but impossible to prove in our logical system. This is what is referred to as incompleteness—the subject of Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem.

The Incompleteness Theorem says that if your logical system can be used to represent arithmetic, then you can come up with a statement that you can neither prove nor disprove.

This is horrible. It means that there are statements we can’t prove in math. There are questions without answers!

Here’s a question without an answer: those of you who have read Harry Potter and the Diagon(alization) Alley might remember that there are more real numbers than integers. The Continuum Hypothesis states that there isn’t a set of numbers that is “bigger” than the integers but “smaller” than the real numbers. It turns out that we can’t prove that. The Continuum Hypothesis is independent of the ZF axioms.

If that sounds a bit abstract, here’s another one: Euclid’s parallel postulate, which says something really obvious about parallel lines, turns out to be independent of his other axioms.

If a line segment intersects two straight lines forming two interior angles on the same side that sum to less than two right angles, then the two lines, if extended indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles sum to less than two right angles.

Finally, the axiom of choice is pretty controversial. Most mathematicians accept it as true, even though it leads to all sorts of weird results. The weirdest one is the Banach-Tarski Paradox, which shows how you can take a sphere, cut it up into five pieces, and reassemble them to get two spheres.

When we talk about ZF with the axiom of choice, we call it ZFC.

- Relate independent statements to the notion of undecidable problems in computer science, such as the halting problem or computing Kolmogorov complexity. Do the proofs of these require some sort of self-referential argument?

As exciting as the Incompleteness Theorems are, there’s a much less celebrated result of Gödel’s called, oddly enough, the Completeness Theorem, published in 1929. It says that there is a rule of inference that is complete (every true statement is provable) for propositional logic.

Gödel did not, however, show what this rule was: we had to wait until 1965 for it. In the next post, we will discover this magical rule of inference, prove its completeness, and show how to use it to write an automatic theorem prover. And we’re going to find out why the title of this post makes sense.

- This post had very few external links. Find a topic you didn’t understand or something you want to learn more about, and look it up.

- Pick 3 things you liked about this post, and 3 things that could be improved. Tell me these things.